The basin contains about 450,000 acres of

wetlands, consisting of 190,000 acres of fresh marsh, 135,000 acres of

intermediate marsh, and 101,000 acres of brackish marsh. A total of 104,380

acres of marsh has converted to open water since 1932, a loss of 19 percent of

the historical wetlands in the basin.

Prior to human alterations, delta-building processes associated with the

Mississippi River resulted in periodic building of marsh along the gulf coast of

the Mermentau Basin. Construction of flood control and navigation projects on

the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers restricted those natural processes to

relatively small portions of the coast. Consequently, marsh-building now occurs

on only the eastern-most portion of the Mermentau Basins coastline. This

condition is further aggravated by continuing subsidence and sea level rise. In

the Mermentau Basin, relative sea level rise results in an average water level

rise of 0.25 inches per year. Although natural wetland building processes only

occur along the eastern shore, natural marsh maintenance processes (e.g., plant

deterioration and regeneration) can be fairly effective at keeping wetland loss

rates low. However, these processes have been altered or interrupted and the

ability of the system to maintain the marsh is jeopardized.

The two subbasins suffer from distinctly different hydrologic problems. The

most critical wetland problem in the Lakes Subbasin is excessive flooding. A

5-mile-long segment of Louisiana Highway 27 almost totally blocks drainage from

the western portion of the Lakes Subbasin into adjacent wetlands of the

Calcasieu/Sabine Basin. Similarly, along the southern boundary of the Lakes

Subbasin, Louisiana Highway 82 blocks drainage across 17 miles of marsh. The

Freshwater Bayou navigation channel has altered the historic drainage pattern in

the eastern portion of the Lakes Subbasin. These numerous blockages of drainage

outlets significantly increase ponding in the subbasin.

The Catfish Point Control Structure, built to reduce saltwater intrusion into

Grand Lake via the Mermentau River, controls the major drainage outlet from the

Lakes Subbasin. High water levels in the gulf frequently prevent the drainage of

the subbasin through the structure. Farther upstream, development and

channelization of the Mermentau River watershed have increased the rate of

run-off into the Lakes Subbasin. These factors, in combination with the loss of

historic drainage outlets, result in periods of prolonged high water levels

following heavy basin-wide precipitation. Because upland drainage improvements

are continuing

Natural freshwater inputs from the Lakes Subbasin into the marshes of the

Chenier Subbasin are reduced by the same highway embankments that impound water

in the northern subbasin. The loss of those freshwater inputs is compounded by

waterways and canals that create additional connections between the gulf and

area marshes, facilitating saltwater intrusion.

Projects in the Mermentau Basin

Summary of the Basin Plan

STUDY AREA

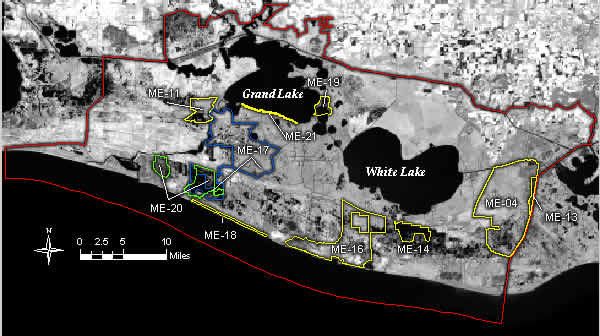

The Mermentau Basin lies in the eastern portion of the Chenier Plain in

Cameron and Vermilion Parishes. The 734,000-acre basin is bounded on the east by

Freshwater Bayou Canal, on the South by the Gulf of Mexico, on the west by

Louisiana State Highway 27, and on the north by the coastal prairie. The Grand

Chenier and Pecan Island ridge systems are linked by Louisiana Highway 82 and

divide the basin into two distinct subbasins: the Lakes Subbasin north of the

highway and the Chenier Subbasin south of the highway (Figure ME-1). About 18

percent (128,200 acres) of the basin lands are publicly owned as Federal refuges

and State wildlife management areas.

EXISTING CONDITIONS AND PROBLEMS

The basin contains about 450,000 acres of wetlands, consisting of 190,000

acres of fresh marsh, 135,000 acres of intermediate marsh, and 101,000 acres of

brackish marsh. A total of 104,380 acres of marsh has converted to open water

since 1932, a loss of 19 percent of the historical wetlands in the basin.

Prior to human alterations, delta-building processes associated with the

Mississippi River resulted in periodic building of marsh along the gulf coast of

the Mermentau Basin. Construction of flood control and navigation projects on

the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers restricted those natural processes to

relatively small portions of the coast. Consequently, marsh-building now occurs

on only the eastern-most portion of the Mermentau Basins coastline. This

condition is further aggravated by continuing subsidence and sea level rise. In

the Mermentau Basin, relative sea level rise results in an average water level

rise of 0.25 inches per year. Although natural wetland building processes only

occur along the eastern shore, natural marsh maintenance processes (e.g., plant

deterioration and regeneration) can be fairly effective at keeping wetland loss

rates low. However, these processes have been altered or interrupted and the

ability of the system to maintain the marsh is jeopardized.

The two subbasins suffer from distinctly different hydrologic problems. The

most critical wetland problem in the Lakes Subbasin is excessive flooding. A

5-mile-long segment of Louisiana Highway 27 almost totally blocks drainage from

the western portion of the Lakes Subbasin into adjacent wetlands of the

Calcasieu/Sabine Basin. Similarly, along the southern boundary of the Lakes

Subbasin, Louisiana Highway 82 blocks drainage across 17 miles of marsh. The

Freshwater Bayou navigation channel has altered the historic drainage pattern in

the eastern portion of the Lakes Subbasin. These numerous blockages of drainage

outlets significantly increase ponding in the subbasin.

The Catfish Point Control Structure, built to reduce saltwater intrusion into

Grand Lake via the Mermentau River, controls the major drainage outlet from the

Lakes Subbasin. High water levels in the gulf frequently prevent the drainage of

the subbasin through the structure. Farther upstream, development and

channelization of the Mermentau River watershed have increased the rate of

run-off into the Lakes Subbasin. These factors, in combination with the loss of

historic drainage outlets, result in periods of prolonged high water levels

following heavy basin-wide precipitation. Because upland drainage improvements

are continuing

Natural freshwater inputs from the Lakes Subbasin into the marshes of the

Chenier Subbasin are reduced by the same highway embankments that impound water

in the northern subbasin. The loss of those freshwater inputs is compounded by

waterways and canals that create additional connections between the gulf and

area marshes, facilitating saltwater intrusion.

FUTURE WITHOUT-PROJECT CONDITIONS

If nothing is done to solve the problem of wetland loss in this basin,

current estimates project a continuing loss rate of 1,980 ares per year. Table

ME-1 shows projected losses for 20- and 50-year periods for each subbasin.

In absence of remedial action, about 18 percent, or 62,900 acres, of the land

in the Lakes Subbasin would be lost over 50 years. This loss would occur in

wetlands adjacent to the shorelines of White and Grand Lakes and the banks of

the GIWW and Freshwater Bayou Canal. Interior losses would continue in the Deep

Lake area, the Freshwater Bayou wetlands, and the vicinity of Little Pecan

Bayou.

Chenier Subbasin wetland losses are projected to be 32 percent, or 36,100

acres, over the next 50 years. Interior wetland losses would continue to occur

south of Pecan Island and Grand Chenier. Erosion along the gulf shoreline would

continue at the present rate of 20 to 40 feet per year.

Table ME-1

Projected Marsh Loss

Projected Loss at 20 yrs. Projected Loss at 50 yrs.

Subbasin (Acres) (Percent) (Acres) (Percent)

Lakes 25,160 7.3 62,900 18.3

Chenier 14,440 12.6 36,100 31.5

Totals 39,600 8.6 99,000 21.4

BASIN PLAN

The short-term portion of the Mermentau Basin plan depends on modifying

existing structures and creating additional outlets to reduce ponding in the

Lakes Subbasin and reducing salinity intrusion in the Chenier Subbasin. In

addition, the plan utilizes shoreline protection, hydrologic restoration, marsh

creation with dredged material, marsh management, terracing, and vegetative

plantings. The long-term portion of the plan relies on hydrologic restoration

and vegetative plantings. Figure ME-2 indicates the strategy for the basin. A

detailed discussion of the plan formulation and evaluation process is in the

Mermentau Basin Plan, Appendix H.

In the Lakes Subbasin, the short-term critical projects use two methods to

move water out of the subbasin for the purpose of reducing flooding stress on

vegetated wetlands: modifying the Vermilion Lock (which is no longer

operational) and the

The short-term supporting projects within the Lakes Subbasin protect interior

wetlands by hydrologic restoration (Sawmill and Humble Canals), rebuild open

water areas (Big Burn and Deep Lake), and protect shorelines and banks (White

Lake, Freshwater Bayou, and the GIWW).

The long-term supporting projects within the Lakes Subbasin treat critical

loss areas by hydrologic restoration ( Miami South Levee and Coteau Plateau

Marsh) and vegetative plantings (Little Pecan Island and along the GIWW).

For the Chenier Subbasin, the short-term critical projects use water

evacuated from the Lakes Subbasin to treat the saltwater intrusion problem

(White Lake Diversion, Grand/White Lake Diversion, and Hog Bayou Freshwater

Introduction).

The short-term supporting projects within the Chenier Subbasin protect the

gulf shoreline from the Mermentau River to the eastern boundary of the

Rockefeller Refuge, restore hydrology (Rollover Bayou Structure), create

wetlands (Pecan Island Terracing), and plant vegetation along the gulf

shoreline.

Table ME-2 lists all the projects in the selected plan. A detailed

description of all projects in the selected plan is contained in Appendix H.

COSTS AND BENEFITS

Lakes Subbasin.

Implementation of the 30 evaluated projects in the selected plan (critical

and supporting short-term projects) will protect, create, or restore 6,710 acres

of wetlands and decrease marsh losses over a period of twenty years by an

estimated 27 percent at a cost of approximately $53,358,000. Three critical

hydrologic restoration projects in the subbasin were not evaluated for cost or

habitat benefits and will require further study and evaluation. The benefits for

these projects will depend on their ability to reduce the water levels in the

subbasin. Additional projects will need to be evaluated for the subbasin for

protection of acreage not covered under the present plan.

Chenier Subbasin.

The selected plan is expected to create, protect, or restore 3,150 acres of

wetlands and reduce marsh loss over a period of twenty years by 22 percent

at a cost of approximately $19,571,000. One project was not evaluated for cost

or habitat benefits and will require further study and evaluation. There is a

need to develop and evaluate other projects to achieve no net loss of wetlands.

If dredging technology becomes more cost-effective, the option of pumping

sediments from the gulf into shallow open water or deteriorating marshes will

need to be investigated. This can only be used in the more saline subbasin

marshes. It should only be done during the spring floods when the gulf

salinities are the lowest in order to avoid placing sediments with higher

salinities into marsh environments.

Back to Top

Dynamics of the Basin

The Mermentau Basin lies in the eastern portion of the chenier plain in

Cameron and Vermilion parishes. This 734,000-acre basin is bounded on the east

by Freshwater Bayou Channel, on the south by the Gulf of Mexico, on the west by

Louisiana Highway 27, and on the north by the GIWW (figure 27). The basin

contains about 450,000 acres of wetlands, consisting predominantly of fresh

(approximately 190,000 acres), intermediate (approximately 135,000 acres), and

brackish marsh (approximately 101,000 acres). The basin is divided into two

distinct subbasins by the Grand Chenier and Pecan Island ridge systems, which

are linked by Louisiana Highway 82. The Lakes subbasin lies to the north, and

includes Grand and White lakes and the GIWW. The Chenier subbasin lies to the

south of Louisiana Highway 82 and includes Hog Bayou, Rockefeller Refuge, and

other marsh areas south of Pecan Island. Wetlands within the Lakes Subbasin

consist primarily of fresh marsh and submergent and floating aquatic vegetation.

Vegetation types within the Chenier Subbasin range from fresh to saline, with

fresh and intermediate marshes existing only in managed areas.

The dominant hydrologic features of the Lakes Subbasin are Grand and White

lakes, with fresh water entering the subbasin through the Mermentau River,

Lacassine Bayou, the Bell City Drainage Canal, the Gueydan Canal, the Warren

Canal, and a number of other smaller drainage canals. Major outlets for

discharge of water from the subbasin include the Catfish Point Control

Structure, the Schooner Bayou Control Structure, the East End Control Structure,

the Leland Bowman Lock, and the Freshwater Bayou Lock. A large number of water

control structures have been constructed at sites where salt water could

encroach into subbasin wetlands, such as in the Little Pecan Bayou area, east of

the Mermentau River.

The hydrology of the Chenier Subbasin is dominated by the Lower Mermentau

River and has been significantly altered through hydrologic management

activities (e.g., for cattle pasture and waterfowl protection). The Mermentau

River-Gulf of Mexico Navigation Channel has altered the hydrology of the river

by connecting the river with the gulf near Grand Chenier. This connection allows

high salinity water from the Gulf of Mexico to enter the Lower Mermentau River.

Drainage for marshes located in the western portion of the subbasin occurs

primarily via access canals and small bayous to the Gulf. The majority of

marshes between Rollover Bayou and Freshwater Bayou Channel drain eastward via

access canals into the Freshwater Bayou Channel.

The Gulf of Mexico beach is retreating across most of the Chenier Subbasin.

However, mud deposits have resulted in a progradation of the eastern shoreline.

The sediment source responsible for this progradation is likely a combination of

reworked Atchafalaya River sediments and reworked spoil from maintenance

dredging of the southern end of Freshwater Bayou Channel. In this prograding

area, the shore consists of a very broad mud flat, colonized by smooth cordgrass

on slightly elevated ridges.

A total of 117,825 acres of marsh have converted to open water since 1932,

which accounts for 18% of the historical wetlands in the Mermentau Basin (Dunbar

et al. 1992) and represents 9% of wetland loss in Louisiana. Current land loss

rates are approximately 2,600 acres/year (Dunbar et al. 1992, Barras et al.

1994). At this rate, approximately 52,000 acres of wetland will be lost during

the next 20 years (an additional 8.6% of the basin's wetlands) without

restorative action (LCWCRTF 1993). This loss is expected to continue along the

shorelines of the lakes and banks of the navigation channels in the Lakes

Subbasin, and in the interior marshes of the Chenier Subbasin (figure 27).

Erosion along the gulf shoreline is expected to continue at its present rate of

20-40 feet per year. Much of the Mermentau Basin's wetland loss is attributed to

saltwater intrusion, ponding, and reductions in freshwater and nutrient inputs.

Louisiana Highway 82 forms a north-south hydrologic barrier between the Lakes

and Chenier subbasins from Oak Grove to Pecan Island, and an east-west

hydrologic barrier between White Lake and Freshwater Bayou. The highway reduces

sheet flow, starves the downstream chenier marshes of fresh water and sediment,

and increases flooding in the Lakes Subbasin.

The most critical wetland problem in the Lakes Subbasin is excessive

flooding. Prolonged high water leads to direct wetland loss and shifts in plant

species composition. High water levels increase erosion rates along natural lake

rims that protect more fragile interior marshes that are lower in elevation.

Once the protective lake rims are lost, erosion rates accelerate. Erosion from

vessel wakes is also a problem along the GIWW and the Freshwater Bayou Channel.

Many areas within the subbasin have experienced marsh loss due to saltwater

intrusion, which mainly impacts areas adjacent to human-made channels and

dredged waterways. In these areas, salt-intolerant plants are destroyed, leaving

marsh soils unprotected. Under these conditions, the subbasin's characteristic

organic soils are easily eroded by tidal movement, resulting in the conversion

of marsh to open water.

In the Chenier Subbasin, the combination of regional and localized hydrologic

alterations associated with numerous access canals and board roads, plus the

failure and abandonment of former forced drainage areas, resulted in extensive

marsh loss. Although input of suspended sediment is currently rebuilding

deteriorated marshes in the westernmost portion of the basin, marshes within the

highly altered middle and upper portions of the basin are continuing to

experience losses. Natural freshwater inputs from the Lakes Subbasin into

marshes of the Chenier Subbasin were virtually eliminated with the construction

of Louisiana highways 27 and 82. The problem is compounded by dredging projects

that create additional connections between the Gulf and subbasin marshes,

facilitating saltwater intrusion. The natural salinity and tidal regime of the

subbasin was altered by the construction of the Freshwater Bayou Channel,

Mermentau River-Gulf of Mexico Navigation Channel, and numerous access canals.

Prior to these alterations, fresh and intermediate marshes were isolated from

tidal exchange and associated high salinities. The introduction of high-salinity

water destroyed much of the vegetation, exposing the underlying organic soils to

tidal exchange, which resulted in extensive marsh loss.

Back to Top

Discussion

In order to successfully protect, restore, and enhance the Mermentau Basin's wetlands, it

is critical that projects be implemented in the Lakes Subbasin to lower water levels and

reduce stress on interior wetlands, and in the Chenier Subbasin to restore freshwater input,

provide additional nutrients and sediment to receiving wetlands, and divert fresh water from

the Lakes Subbasin. Implementation of projects that reduce interior wetland loss, rebuild

wetlands in open water areas, and maintain the geologic framework of the basin by addressing

shoreline erosion along the lakes, navigation channels, and gulf, is also critical. Although

it is too early to determine the success of the all CWPPRA projects, preliminary indications

for completed projects' goals are being met. Although the vegetative plantings failed for the

Dewitt-Rollover project, deauthorization of this project has released funds which had been

reserved for maintenance and monitoring of the project so that these funds can be spent on

more appropriate efforts. The anticipated benefits of current and future CWPPRA projects,

along with complementary state sponsored projects, should help to maintain the integrity of

Mermentau Basin wetlands.