The Barataria Basin is an irregularly shaped area bounded on each side by a distributary ridge formed by

the present and a former channel of the Mississippi River. A chain of barrier

islands separates the basin from the Gulf of Mexico. In the northern half of the

basin, which is segregated by the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW), several

large lakes occupy the sump position approximately half-way between the ridges.

The southern half of the basin consists of tidally influenced marshes connected

to a large bay system behind the barrier islands. The basin contains 152,120

acres of swamp, 173,320 acres of fresh marsh, 59,490 acres of intermediate

marsh, 102,720 acres of brackish marsh, and 133,600 acres of saline marsh.

Within the Barataria Basin, wetland loss rates averaged nearly 5,700 acres

per year between 1974 and 1990. During this period, the highest rates of loss

occurred in the Grande Cheniere and Bay Regions. Wetland loss within the

Barataria Basin is attributed to the combination of natural erosional processes

of sea-level rise, subsidence, winds, tides, currents, and herbivory, and the

human activities of channelization, levee construction, and development.

Freshwater and sediment input to the Barataria Basin was virtually eliminated

by the erection of flood protection levees along the Mississippi River and the

closure of Bayou Lafourche at Donaldsonville; therefore, the only significant

source of fresh water for the basin is rainfall. Only a small amount of riverine

input, designed to mimic a natural crevasse, is introduced into the basin's

wetlands through the recently completed siphons at Naomi and West Pointe a la

Hache. This lack of fresh water, and the loss of the accompanying sediments,

nutrients, and hydrologic influence, forms the most critical problem of the

Barataria Basin.

The second critical problem is the erosion of the barrier island chain. As

individual islands are reshaped or breached, or succumb to the forces of the

Gulf of Mexico, passes widen and deepen with the result that a greater volume of

water is exchanged during each tide.

Four islands-West Grand Terre, East Grand Terre, Grand Pierre, and Cheniere

Ronquille-had a combined area of just over 1,800 acres in 1990. By 2015, the

islands will be reduced to a total of approximately 1,000 acres. East Grand

Terre and Grand Pierre are predicted to disappear by 2045, and the remaining

islands will consist of only 400 acres.

The result of the problems described above is an increase in tidal amplitude

in the marshes in the central basin. This cumulative effect is exemplified by

increased salinities in the lower half of the basin, increased land loss rates,

and change in vegetation.

Site-specific problems of shoreline erosion, especially in areas with organic

soils, poor drainage, salinity stress, and herbivory, are apparent throughout

the basin. Solving these problems is important, but less urgent than solving the

critical problems described above.

Projects in the Barataria Basin

Summary of the Basin Plan

STUDY AREA

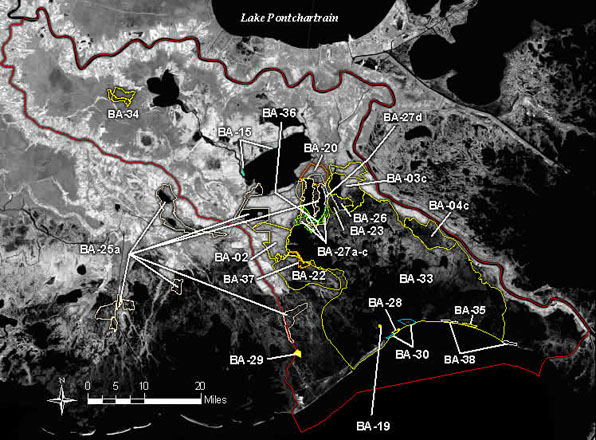

The Barataria Basin (Figure BA-1) is located immediately south and west of

New Orleans, Louisiana. The basin is bounded on the north and east by the

Mississippi River from Donaldsonville to Venice, on the south by the Gulf of

Mexico, and on the west by Bayou Lafourche. The basin contains approximately

1,565,000 acres. Portions of nine parishes are found in the basin: Assumption,

Ascension, St. James, Lafourche, St. John the Baptist, St. Charles, Jefferson,

Plaquemines, and Orleans. The basin is divided into nine subbasins: Fastlands,

Des Allemands, Salvador, Central Marsh, Grande Cheniere, L'Ours, North Bay, Bay,

and Empire.

EXISTING CONDITIONS AND PROBLEMS

The Barataria Basin is an irregularly shaped area bounded on each side by a

distributary ridge formed by the present and a former channel of the Mississippi

River. A chain of barrier islands separates the basin from the Gulf of Mexico.

In the northern half of the basin, which is segregated by the Gulf Intracoastal

Waterway (GIWW), several large lakes occupy the sump position approximately

half-way between the ridges. The southern half of the basin consists of tidally

influenced marshes connected to a large bay system behind the barrier islands.

The basin contains 152,120 acres of swamp, 173,320 acres of fresh marsh, 59,490

acres of intermediate marsh, 102,720 acres of brackish marsh, and 133,600 acres

of saline marsh.

Within the Barataria Basin, wetland loss rates averaged nearly 5,700 acres

per year between 1974 and 1990. During this period, the highest rates of loss

occurred in the Grande Cheniere and Bay Regions. Wetland loss within the

Barataria Basin is attributed to the combination of natural erosional processes

of sea-level rise, subsidence, winds, tides, currents, and herbivory, and the

human activities of channelization, levee construction, and development.

Freshwater and sediment input to the Barataria Basin was virtually eliminated

by the erection of flood protection levees along the Mississippi River and the

closure of Bayou Lafourche at Donaldsonville; therefore, the only significant

source of fresh water for the basin is rainfall. Only a small amount of riverine

input, designed to mimic a natural crevasse, is introduced into the basin's

wetlands through the recently completed siphons at Naomi and West Pointe a la

Hache. This lack of fresh water, and the loss of the accompanying sediments,

nutrients, and hydrologic influence, forms the most critical problem of the

Barataria Basin.

The second critical problem is the erosion of the barrier island chain. As

individual islands are reshaped or breached, or succumb to the forces of the

Gulf of Mexico, passes widen and deepen with the result that a greater volume of

water is exchanged during each tide.

Four islands-West Grand Terre, East Grand Terre, Grand Pierre, and Cheniere

Ronquille-had a combined area of just over 1,800 acres in 1990. By 2015, the

islands will be reduced to a total of approximately 1,000 acres. East Grand

Terre and Grand Pierre are predicted to disappear by 2045, and the remaining

islands will consist of only 400 acres.

The result of the problems described above is an increase in tidal amplitude

in the marshes in the central basin. This cumulative effect is exemplified by

increased salinities in the lower half of the basin, increased land loss rates,

and change in vegetation.

Site-specific problems of shoreline erosion, especially in areas with organic

soils, poor drainage, salinity stress, and herbivory, are apparent throughout

the basin. Solving these problems is important, but less urgent than solving the

critical problems described above.

FUTURE WITHOUT-PROJECT CONDITIONS

Projected wetland loss over the next 20 and 50 years within Barataria Basin,

by the subbasins, is shown in Table BA-1. Without actions to correct the

problems mentioned above, another fifth of the basin's wetlands would be lost to

open water by 2045. Roughly 65 percent of the projected wetland loss, or

more than 100,000 acres, would occur in the North Bay, L'Ours, Bay, and Empire

subbasins. As wetlands bordering Barataria Bay erode and as its connection with

the gulf becomes substantially larger because of the disappearance of the

barrier islands, the bay would enlarge, absorbing adjacent waterbodies. With no

action, moderate wetland losses (about 20 percent) would occur in the

middle of the basin (Central Marsh and Salvador subbasins), and relatively minor

losses (about 8 percent) would occur in the upper basin (Des Allemands)

over the next 50 years. The disappearance of wetlands throughout Barataria Basin

would mean the loss of critical breeding, nesting, nursery, foraging, or

overwintering habitat for economically important fish, shellfish, furbearers,

migratory waterfowl, alligator, and several endangered species. Loss of wetland

habitat and the accompanying trend toward higher salinities would lead to lower

biodiversity and productivity.

Table BA-1

Projected Marsh Loss in the Barataria Basin.

Projected Loss in 20 years Projected Loss in 50 years

Subbasin (Acres) (Percent) (Acres) (Percent)

Des Allemands 1,010 3 2,520 7

Salvador 4,610 4 11,540 11

Central 7,380 10 18,440 26

L'Ours 6,240 21 15,590 53

North Bay 10,160 12 25,390 31

Grand Chenier 6,510 44 14,660 100

Empire 17,460 58 30,110 100

Bay 22,790 28 56,980 70

Total 76,160 17 175,230 38

Projected losses are based on Geographic Information System data compiled by

the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Loss rates also are based on a projection of

the 1974 to 1990 rates.

The disappearance of wetlands and the wildlife and fishery resources

dependent on them would affect the economic structure of numerous communities in

the lower and middle basin areas as supporting businesses (marinas, boat

manufacturers, seafood processors, retailers, etc.) decline. In addition, the

storm buffering benefits the barrier islands and lower basin wetlands provide these

communities, would be reduced as wetland loss continues. This loss would force

relocations or require the expansion of flood protection and drainage facilities

for many basin communities, and maintenance costs would increase for existing

facilities.

BASIN PLAN

The selected plan focuses on the key strategies of freshwater and sediment

diversion, combined with outfall and hydrologic management to reduce tidal

exchange. Two additional mutually exclusive strategies were considered to offset

the increase in tidal amplitude: sediment replenishment of the existing barrier

islands or construction of a set of interior barrier islands. The former has

been included in the selected plan because it supports the natural system, and

would maintain the marshes located between the proposed interior barrier and the

existing barrier islands. Supporting strategies of marsh creation with dredged

material and shoreline protection address localized areas of marsh loss. A

detailed description of the plan formulation process is contained in Appendix D.

Strategies of the selected basin plan are shown in Figure BA-2, and projects are

listed in Table BA-2.

Restoration of riverine input into the basin via freshwater diversion from

the Mississippi River through the authorized Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion

project helps in solving the first critical problem of freshwater and sediment

deprivation. This diversion is vital to the health of the upper part of the

basin because fresh water and nutrients slow the loss of marsh and swamp.

Additional diversions from the Mississippi River on the eastern side of the

basin, and the reconnection of Bayou Lafourche and subsequent construction of

small diversions on the western side, are long-term solutions to the first

critical problem. However, a study of the sediment and water budget for the

Mississippi River must be completed first.

Sediment replenishment and marsh creation on the bay side of the barrier

islands will strengthen the buffering capabilities of the barrier chain.

Longshore sediment drift studies will determine the efficacy of installing

segmented breakwaters or jetties to trap sediments that are, at present,

transported from the system. Studies are planned on methods to reduce the cost

of construction and to better evaluate the benefits of barrier islands to

interior marshes. However, sediment replenishment of critical barrier islands

(located adjacent to major tidal passes) needs to be implemented in the short

term.

Hydrologic management to decrease tidal flux through the critical area of the

central marshes and LOurs Ridge will preserve the marshes in this area and

slow the inland progression of the marine influence. Methods to reduce marsh

loss rates and shoreline erosion, while providing access to the

estuarine-dependent marine organisms so important to the economy of this basin,

should be developed and implemented as soon as possible.

Several site-specific areas of loss are scattered throughout the basin.

Small-scale measures to preserve, restore, and enhance these marshes and swamps

are important. Implementation of these projects will maintain these areas until

the critical long-term projects are in place.

The selected plan uses a mix of measures to achieve short-term basin

objectives. Hydrologic restoration (77 percent), outfall management (8 percent),

and barrier island nourishment (6 percent) account for the majority of the

acres preserved, created, or enhanced. Marsh creation with dredged material,

shoreline protection, and marsh management complete the short-term restoration

process. The long-term portion of the plan, necessary to achieve no net loss of

wetlands, consists of additional freshwater and sediment diversions, and

continued barrier island replenishment.

COSTS AND BENEFITS

Table BA-3 summarizes the wetland benefits and costs over the next 20 years

for the short-term projects proposed in the Barataria Basin selected plan and

for the Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion project. The Davis Pond Freshwater

Diversion project will preserve 83,000 acres over 50 years at a cost of $68.8

million. However, to be comparable to the CWPPRA projects, benefits and costs

for 20 years (32,220 acres and $26,696,000) were used.

In the Des Allemands Subbasin, no direct benefits are achieved because there

are no selected plan short-term projects and Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion is

located south of the subbasin. However, this area will indirectly benefit from

plan implementation because significant portions of the seaward subbasins will

be restored or maintained, thus providing a continued barrier to the inland

progression of marine influence.

Implementation of the short-term projects in the Salvador Subbasin would

prevent 28 percent of the predicted loss. In the Central Marsh Subbasin,

implementation of already funded projects BA-2, PBA-35, and XBA-65A, plus the

deferred project BA-6, would result in predicted marsh enhancement of 177 percent.

When estimated Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion benefits are added to the

Salvador and Central Marsh Subbasins, marsh enhancement increases to 337 and 281 percent,

respectively. The CWPPRA costs are $39,889,000.

Plan implementation would prevent 12, 13 and 55 percent of the predicted

loss in the L'Ours, North Bay and Grande Cheniere Subbasins. The projects

located in this mid-basin area are designed to protect wetlands against tidal

and erosive forces. Adding the Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion benefits to the

North Bay Subbasin prevents 75 percent of the predicted loss. The CWPPRA

costs for this area are $8,344,000.

The lower basin marshes and barrier islands which make up the Empire and Bay

Subbasins are projected to undergo the greatest losses. Plan implementation

would only reduce the losses in these areas by 5 and 8 percent, respectively.

The Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion project would prevent the loss of an

additional 17 percent of wetlands in the Bay Subbasin. The CWPPRA costs are

$66,425,000.

For a total expenditure of $114,658,000 on the selected plan projects, 23,050

acres of wetlands will be created, restored or protected. Over the next 20

years, 30 percent of predicted loss in the entire Barataria Basin would be

prevented. Benefits from the Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion project increases

the predicted amount of marsh saved to 73 percent, including gains in two

subbasins.

Back to Top

Dynamics of the Basin

Located south and west of New Orleans, the Barataria Basin is bounded on the

north and east by the Mississippi River, on the west by Bayou Lafourche, and on

the south by the Gulf of Mexico (figure 21). The basin is approximately 120

miles long, with a width ranging from 24 to 35 miles. The basin contains

approximately 1,565,000 acres, of which 341,500 acres (22%) are leveed or

developed areas. The region contains major corridors of developed areas along

the Mississippi River and Bayou Lafourche. While most of the land is privately

owned, two wildlife management areas and one national park with a total of

65,000 acres are located within the basin.

Several natural and constructed physiographic features in Barataria Basin

influence habitat distribution, hydrology, land use, and wetland restoration

opportunities. Major features include natural and artificial levees of the

Mississippi River and Bayou Lafourche, the GIWW, U.S. Highway 90, the central

marsh landmass, the chenier complex, and a chain of barrier islands. The island

chain is eroding and will continue to deteriorate unless restorative measures

are implemented. The USACE maintains major navigation channels in the basin.

These include the Barataria Bay Waterway, which runs from Barataria Pass at

Grand Isle to the GIWW south of Lake Salvador; the GIWW, which runs east-west

through the central reaches of the basin; and the Empire-Gulf Waterway, which

runs from the gulf to the Mississippi River in southeast Barataria. All are

major navigation routes for the oil and gas industry, the sulphur industry, and

commercial and recreational fishing. Sediment deposited by the Mississippi River

in the former St. Bernard and Lafourche deltas filled the margins of the Gulf of

Mexico and built these marshes over the last several thousand years (Frazier

1967). These marshes received periodic inputs of sediment and fresh water from

the Mississippi River until the early 1900s but are now isolated from the river.

Although there is currently no river discharge into these marshes, extensive

non-saline marshes exist where water exchange with the gulf is restricted,

primarily because average rainfall (162 centimeters/year) exceeds average

evapotranspiration (102 centimeters/year) in southeast Louisiana (Newton 1972).

Water volumes and water levels in the basin are strongly influenced by tides,

winds, and precipitation. Tides of the northern gulf have a relatively small

range between high and low, measuring 1 foot in the gulf and 0.1 foot in the

upper basin (LCWCRTF 1993). Storm tides can account for more than half of the

daily water level fluctuations in the basin (Jarrett 1976, Levin 1990). Water

exchange within the basin is highly variable (Richie 1985, Richie and Penland

1989). The dominant water exchange route between the upper and lower basin is

through Little Lake, Bayou Perot, and Lake Salvador.

Since 1932, Bararataria Basin has lost almost 17% of its land area (Dunbar et

al. 1992). Recent annual wetland loss estimates in Barataria Basin range between

5,200 (Dunbar et al. 1992) and 7,100 (Barras et al. 1994) acres per year (figure

21). At this rate, Barataria Basin will lose up to 142,340 acres of land during

the next 20 years-a loss greater than that in any other basin in Louisiana's

coastal zone. The subsidence rate in the Barataria Basin, based on USACE tide

gage readings (1947-78) at Bayou Rigaud, Grand Isle, Louisiana, is 0.80

centimeters (0.03 inches)/year (Penland et al. 1989).

Without actions to correct the land loss and habitat degradation in the

Barataria Basin, another fifth of the basin's wetlands may be converted to open

water by the year 2045. Approximately 65% of wetland loss would be concentrated

in the southern half of the basin. The Barataria Bay would enlarge, absorbing

adjacent water bodies, and its connection with the Gulf would become

substantially larger as barrier islands disappear. As a result of continued

erosion of the barrier island chain, the tidal passes will enlarge and deepen,

reducing the potential hydrologic benefits of the islands to the basin.

Back to Top

Discussion

All of the restoration projects planned for the Barataria Basin support the objectives and

strategies outlined for the basin. Both outfall management projects support the strategy of

managing freshwater and sediment input and enhancing fringe marshes in the basin. Continued

emphasis on fresh water diversion from the Mississippi River is also of prime importance.

The potential seems to exist not only to stop wetland loss, but to build new marsh through

sediment and fresh water reintroduction into the Barataria Basin.