The three large lakes, Maurepas,

Pontchartrain, and Borgne cover 55 percent of the basin. Lakes Maurepas and

Pontchartrain are separated by land bridges of cypress swamp and

fresh/intermediate marsh. A brackish marsh land bridge separates Lake

Pontchartrain from Lake Borgne.

The basin contains 483,390 acres of wetlands, consisting of nearly 38,500

acres of fresh marsh, 28,600 acres of intermediate marsh, 116,800 acres of

brackish marsh, 83,900 acres of saline marsh, and 215,600 acres of cypress

swamp. Since 1932, more than 66,000 acres of marsh have converted to water in

the Pontchartrain Basin--over 22 percent of the marsh that existed in 1932. The

primary causes of wetland loss in the basin are the interrelated effects of

human activities and the estuarine processes that began to predominate many

hundreds of years ago, as the delta was abandoned.

The Mississippi River levees significantly limit the input of fresh water,

sediment, and nutrients into the basin. This reduction in riverine input plays a

part in the major critical problem in the Pontchartrain Basin--increased

salinity. Construction of the MRGO, which breaches the natural barrier of the

Bayou La Loutre ridge and the Borgne land bridge, allowed saline waters to push

farther into the basin. Relative sea level rise of up to 0.96 feet per century

gives saltier waters greater access to basin wetlands. Mean monthly salinities

have increased since the construction of the MRGO and other canals. However,

these mean increases are less than the overall variability in salinity. In

recent years, salinities have stabilized. The heightened salinity, caused mainly

by subsidence, stresses wetlands, especially fresh marsh and swamp.

A second critical problem, occurring in the lower basin, is the erosion along

the MRGO caused by ship-induced waves. The channel's north bank continues to

eroding at a rate of 15 feet per year. This mechanism has resulted in the direct

loss of over 1,700 acres of marsh since 1968.

The third critical problem is the potential loss of the Borgne and the

Maurepas land bridges where wetland soils are especially vulnerable to erosion.

Since 1932, approximately 24 percent of the Borgne Land Bridge has been lost to

estuarine processes such as severe shoreline retreat and rapid tidal

fluctuations, and the loss rate is increasing. During the same time, 17 percent

of the Maurepas Land Bridge marshes disappeared due to subsidence and spikes in

lake salinity. In addition, from 1968 to 1988, 32 percent of the cypress swamp

on this land bridge either converted to marsh or became open water. These land

bridges prevent estuarine processes, such as increased salinities and tidal

scour, from pushing further into the middle and upper basins. If these buffers

are not preserved, the land loss rates around Lakes Pontchartrain and Maurepas

will increase dramatically.

The fourth critical problem is that several marshes in the basin are

vulnerable to rapid loss if adequate protection is not provided soon. Examples

of theses areas are: marshes adjacent to lakes and bays where if the narrow rim

of shore is lost, interior erosion will increase dramatically; the perched fresh

marsh on the MRGO disposal area which will drain and revegetate with shrub

unless the back levee dikes are repaired; and near Bayou St. Malo, where unless

canals are plugged, rapid water level fluctuations and salinity intrusion into

adjacent marshes will continue.

Site specific problems of shoreline erosion, poor drainage, salinity stress,

and herbivory are apparent throughout the basin. Solving these problems is

important, but less urgent than solving the four critical problems described

above.

Projects in the Potchartrain Basin

Summary of the Basin Plan

STUDY AREA

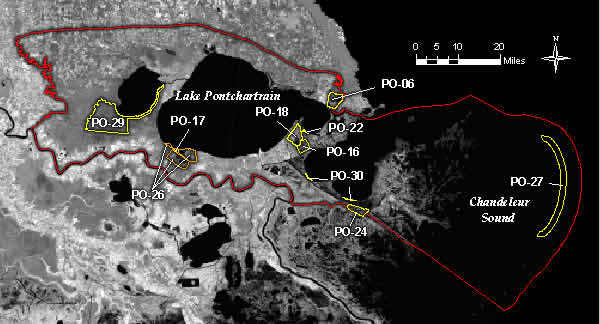

The 1,700,000-acre Pontchartrain Basin is an abandoned delta generally

bounded by the Pleistocene Terrace on the north and west, by Chandeleur Sound on

the east, and by the Mississippi River and the disposal area of the Mississippi

River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) on the south. Portions of nine parishes lie within the

basin: Ascension, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Charles, Jefferson,

Orleans, St. Bernard, St. Tammany, and Livingston. The basin is divided into six

distinct areas: the upper, middle, lower, and Pearl basins, and the Lake

Maurepas/Pontchartrain and Lake Pontchartrain/Borgne land bridges (Figure PO-1).

Approximately 17 percent of the land in the basin is in public ownership.

EXISTING CONDITIONS AND PROBLEMS

The three large lakes, Maurepas, Pontchartrain, and Borgne cover 55 percent

of the basin. Lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain are separated by land bridges of

cypress swamp and fresh/intermediate marsh. A brackish marsh land bridge

separates Lake Pontchartrain from Lake Borgne.

The basin contains 483,390 acres of wetlands, consisting of nearly 38,500

acres of fresh marsh, 28,600 acres of intermediate marsh, 116,800 acres of

brackish marsh, 83,900 acres of saline marsh, and 215,600 acres of cypress

swamp. Since 1932, more than 66,000 acres of marsh have converted to water in

the Pontchartrain Basin--over 22 percent of the marsh that existed in 1932. The

primary causes of wetland loss in the basin are the interrelated effects of

human activities and the estuarine processes that began to predominate many

hundreds of years ago, as the delta was abandoned.

The Mississippi River levees significantly limit the input of fresh water,

sediment, and nutrients into the basin. This reduction in riverine input plays a

part in the major critical problem in the Pontchartrain Basin--increased

salinity. Construction of the MRGO, which breaches the natural barrier of the

Bayou La Loutre ridge and the Pontchartrain/Borgne land bridge, allowed saline

waters to push farther into the basin. Relative sea level rise of up to 0.96

feet per century gives saltier waters greater access to basin wetlands. Mean

monthly salinities have increased since the construction of the MRGO and other

canals. However, these mean increases are less than the overall variability in

salinity. In recent years, salinities have stabilized. The heightened salinity,

caused mainly by subsidence, stresses wetlands, especially fresh marsh and

swamp.

A second critical problem, occurring in the lower basin, is the erosion along

the MRGO caused by ship-induced waves. The channel's north bank continues to

eroding at a rate of 15 feet per year. This mechanism has resulted in the direct

loss of over 1,700 acres of marsh since 1968.

The third critical problem is the potential loss of the Pontchartrain/Borgne

and the Pontchartrain/Maurepas land bridges where wetland soils are especially

vulnerable to erosion. Since 1932, approximately 24 percent of the

Pontchartrain/Borgne Land Bridge has been lost to estuarine processes such as

severe shoreline retreat and rapid tidal fluctuations, and the loss rate is

increasing. During the same time, 17 percent of the Pontchartrain/Maurepas Land

Bridge marshes disappeared due to subsidence and spikes in lake salinity. In

addition, from 1968 to 1988, 32 percent of the cypress swamp on this land bridge

either converted to marsh or became open water. These land bridges prevent

estuarine processes, such as increased salinities and tidal scour, from pushing

further into the middle and upper basins. If these buffers are not preserved,

the land loss rates around Lakes Pontchartrain and Maurepas will increase

dramatically.

The fourth critical problem is that several marshes in the basin are

vulnerable to rapid loss if adequate protection is not provided soon. Examples

of theses areas are: marshes adjacent to lakes and bays where if the narrow rim

of shore is lost, interior erosion will increase dramatically; the perched fresh

marsh on the MRGO disposal area which will drain and revegetate with shrub

unless the back levee dikes are repaired; and near Bayou St. Malo, where unless

canals are plugged, rapid water level fluctuations and salinity intrusion into

adjacent marshes will continue.

Site specific problems of shoreline erosion, poor drainage, salinity stress,

and herbivory are apparent throughout the basin. Solving these problems is

important, but less urgent than solving the four critical problems described

above.

FUTURE WITHOUT-PROJECT CONDITIONS

If nothing is done, and marsh loss continues at the pace set from 1974-1990,

another 62,400 acres, or 23 percent of the basin's existing marshes, would be

lost by the year 2040, as displayed in Table PO-1. If no action is taken, 69,400

acres of swamp, 32 percent of the basin's existing swamp, would be converted to

marsh or open water by 2040. This does not include the possible loss of the

upper basin swamps. As the land bridges are lost, estuarine processes would push

farther into the basin and erosion rates would increase. The middle basin would

be a lake surrounded by shallow ponds where marshes once existed. The lower

basin marshes would be a tattered remnant of what exists today. Fewer fish and

shellfish would be available for commercial or recreational fishermen. Vast

marshes for wintering ducks would no longer exist. The emerging ecotourism

industry would be hindered, and storm surge protection would be lost as lakes

and bays inched closer to levees and roads.

Table PO-1

Projected Marsh and Swamp Loss

Projected Loss in 20 years Projected loss in 50 years

Subbasin (Acres) (Percent) (Acres) (Percent)

Upper Basin

Swamp 0 0 0 0

Pontchartrain/Maurepas Land Bridge

Swamp 23,200 38 58,000 95

Marsh 1,320 6 3,300 15

Middle Basin

Swamp 9,600 62 11,400 74

Marsh 3,800 12 9,500 30

Pontchartrain/Borgne Land Bridge

Marsh 4,560 10 11,400 30

Lower Basin

Marsh 14,580 9 36,450 24

Pearl River Basin

Marsh 700 4 1,750 10

Total Swamp Loss 32,800 15 69,400 32

Total Marsh Loss 24,960 9 62,400 23

Insert Figure PO-1. Pontchartrain Basin, Basin and Subbasin Boundaries.

Back of Figure PO-1. Pontchartrain Basin, Basin and Subbasin Boundaries.

BASIN PLAN

The main strategies of the basin plan are shown in Figure PO-2. Restoration

of riverine input into the basin via freshwater diversion from the Mississippi

River through the Bonnet Carr Spillway solves the first critical problem,

salinity. This is preferred to the strategy of a navigable gate in the MRGO

because the diversion has the added benefit of restoring fluvial input and is

less costly overall and on a per-acre basis. The project is already authorized

and need not be funded under the CWPPRA. An outfall management plan for the

diversion is critical. Construction of a rock dike on the north bank of the MRGO

and the beneficial use of all the material dredged for the MRGO would stop

erosion, addressing the second critical problem, and create large amounts of

marsh. The diversion at the Bonnet Carr Spillway and bank protection with

marsh creation along the MRGO are critical projects.

Additional short-term projects include the following.

- Preservation of the land bridges through shoreline protection, hydrologic

restoration, and marsh management solves the third critical problem. Various

critical projects reduce future marsh loss rates and prevent estuarine processes

from pushing farther into Lakes Pontchartrain and Maurepas.

- Preservation of the several marshes in the basin which are immediately

vulnerable to loss is crucial to resolving the fourth critical problem. Projects

which protect shorelines in several critical areas, preserve the fresh marshes

on the MRGO disposal area, and retain the brackish marshes in the St. Malo area

all require quick implementation.

- Several site specific areas of loss are scattered throughout the basin.

Small-scale measures to preserve, restore, and enhance these marshes and swamps

are important. These supporting projects should be considered once the more

critical projects are in place.

In the long term, getting more fresh water and nutrients into the basin is

critical. Five small-scale freshwater diversions into swamps and marshes of the

basin are proposed. First, however, a study on the sediment and water budget for

the Mississippi River must be completed.

Going beyond these diversions to achieve no net loss of wetlands in the

long-term depends on cost-effective importation of sediment either by diversions

or by dedicated dredging with dispersal by barging or pipelines. This critical

long-term strategy could significantly reduce wetland loss in the basin, but it

is very costly at this time.

Creation of artificial barrier islands could preserve the outer saline

marshes. Although expensive, it is defined as critical and retained in the

selected plan for possible implementation in the long term. Studies are planned

on methods to reduce the cost of construction and to better evaluate benefits to

interior marshes. If costs can be reduced and benefits increased, priority for

implementing this strategy will increase.

The selected plan uses a combination of measures to achieve basin objectives.

Projects accounting for the majority of the acres preserved or created are

distributed in the following manner: hydrologic restoration (27%), freshwater

diversion/outfall management (28%), shoreline protection (24%), and marsh

creation (18%).

In summary, the short-term portion of the basin plan consists of the

freshwater diversion at the Bonnet Carr Spillway and bank protection and marsh

creation along the MRGO complemented by the preservation of the land bridges,

critical areas, and other wetlands using numerous hydrologic restoration, marsh

creation, and shoreline protection projects. The long-term portion of the plan,

necessary to achieve a no net loss of wetlands, consists of additional

freshwater diversions, sediment import, and the creation of barrier islands.

Projects included in the Pontchartrain Basin Plan are listed in Table PO-2.

The table provides the classification (e.g., critical, supportive,

demonstration), estimated benefits and costs, and status of these projects. A

complete listing of all the projects proposed for the Pontchartrain Basin can be

found in Appendix A, Table 8. More detailed information on each project is also

included in Appendix A.

COSTS AND BENEFITS

An expenditure of $132,738,000 on short-term projects and $72,000,000 on

construction and 20 years of maintenance of the Bonnet Carr Freshwater

Diversion will create or preserve 17,320 acres of marsh and 3,600 acres of swamp

and thus prevent 69 percent of the marsh loss and 7 percent of the swamp loss in

the Pontchartrain Basin (see Table PO-3).

As shown in the table, short-term projects prevent 83 to 92 percent of the

future marsh loss on the land bridges and achieve no net loss of marsh in the

middle basin. However the plan prevents only 44 percent of the marsh loss in the

lower basin. Clearly, additional long-term efforts are needed to preserve these

eroding marshes. Construction of the artificial barrier islands prevents the

loss of an additional 33 percent of the lower basin. However, the cost of

barrier island creation, using present technology, is an additional $600

million. Long-term sediment import projects are essential in achieving no net

loss in the lower basin. Sediment import into the upper basin is necessary to

begin to preserve its cypress swamps. The cost of these sediment import projects

is unknown. Thus, complete restoration of the upper and lower basins requires

investigation of cost effective techniques to build barrier islands and import

sediment.

Back to Top

Dynamics of the Basin

The Pontchartrain Basin contains approximately 1.7 million acres and is

bounded by the Pleistocene Terraces on the north and west, by Chandeleur Sound

on the east, and by the Mississippi River and the disposal area of the

Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) on the south (figure 17). The marshes are

primarily privately owned (625,000 acres); however, some extensive areas are

managed as a federal wildlife refuge (25,400 acres) or as state wildlife

management areas (100,000 acres). The basin is part of the abandoned St. Bernard

delta and has approximately 935,000 acres (56%) of open water within its

boundary. The remaining 44% of the Pontchartrain Basin is composed of 13%

cypress/tupelo swamp, 2% fresh marsh, 2% intermediate marsh, 7% brackish marsh,

5% saline marsh, and 15% other land.

The major hydrologic features of the basin are Lakes Maurepas, Pontchartrain,

and Borgne, and Chandeleur Sound. Lake Pontchartrain is connected to Lake

Maurepas to the west and Lake Borgne to the east by passes through interlying

land bridges (i.e., a land area separating two hydrologic features). The Inner

Harbor Navigation Canal (IHNC) and the MRGO provide a direct link between Lake

Pontchartrain and the Gulf of Mexico. Historically, fresh water entered the

Pontchartrain Basin through Bayou Manchac (until its closure in 1812) and from

natural crevasses from the Mississippi River (until construction of the Mississippi River

levees in the 1930s). Fresh water now enters the basin through leaks in the

Bonnet Carr Spillway, through the IHNC Lock, the Violet Siphon, numerous small

rivers and bayous (totaling approximately 9,500 cfs), and from direct rainfall.

Urban storm water discharges from the New Orleans metropolitan area also enter

Lake Pontchartrain.

Since 1932, over 76,000 acres of marsh (almost 8% of the basin's land area)

have converted to open water in the Pontchartrain Basin (Dunbar et al. 1992,

figure 17). Based on current loss rates, approximately 1,250 acres of marsh will

continue to be lost each year without restorative action (Dunbar et al. 1992,

Barras et al. 1994) . This loss amounts to approximately 25,000 acres during the

next 20 years. If no action is taken to restore and protect the remaining

wetlands, it is projected that an additional 23% will be lost by the year 2040

(LCWCRTF 1993).

Back to Top

Discussion

All of the approved CWPPRA projects in the Pontchartrain Basin contribute to the restoration objectives

previously listed. One project, the Violet Freshwater Distribution Project, manages fresh water to

reduce salinity and preserve marsh and swamp. The MRGO Back Dike Marsh Protection project will preserve

marsh within an existing spoil disposal area. Two projects, Bayou Sauvage Phases I and II, improve

hydrology and manage marshes on the land bridges between Lake Pontchartrain and Lakes Maurepas

(on the west) and Borgne (on the east). The Fritchie Marsh project restores wetlands where loss is

imminent. The Bayou Chevee and Bayou La Branche projects beneficially use dredged material to create

marsh. Preliminary results from the Bayou La Branche wetland creation project indicates that this project

is already successful at creating new wetlands in the Pontchartrain Basin (Carriere 1996a). The Eden

Isle project will restore former marsh and regulate water levels to prevent excessive inundation from

Lake Pontchartrain, while the Red Mud Demonstration project will examine some of the issues and concerns

regarding the use of this waste material for marsh creation on a small scale.