The Terrebonne Basin is an abandoned delta

complex, characterized by a thick section of unconsolidated sediments that are

undergoing dewatering and compaction, contributing to high subsidence, and a

network of old distributary ridges extending southward from Houma. The southern

end of the basin is defined by a series of narrow, low-lying barrier islands

(the Isles Dernieres and Timbalier chains), separated from the mainland marshes

by a series of wide, shallow lakes and bays (e.g., Lake Pelto, Terrebonne Bay,

Timbalier Bay).

The Verret and Penchant Subbasins receive fresh water from the Atchafalaya

River and Bay, while the Fields Subbasin gets fresh water primarily from

rainfall. The Timbalier Subbasin gets fresh water from rainfall and from

Atchafalaya River inflow to the GIWW via the Houma Navigation Canal (HNC) and

Grand Bayou Canal; it has the most limited fresh water resources in the entire

Deltaic Plain.

The Terrebonne Basin supports about 155,000 acres of swamp and almost 574,000

acres of marsh, grading from fresh marsh inland to brackish and saline marsh

near the bays and the gulf. The Verret Subbasin contains most of the cypress

swamp (118,000 acres) in the Terrebonne Basin. The northern Penchant Subbasin

supports extensive fresh marsh (about 166,000 acres), including a predominance

of flotant marsh, with 98,000 acres of intermediate and brackish marsh in the

Lost Lake-Jug Lake area and about 17,000 acres of saline marsh to the south.

Fresh marsh is also dominant in the Fields Subbasin (approximately 23,000

acres). The Timbalier Subbasin grades from fresh marsh in the northern part of

the subbasin to saline marsh near the bays, but is dominated by brackish (71,000

acres) and saline (153,000 acres) marsh types.

Of the four subbasins, only the Fields Subbasin experiences problems which

are local and relatively minor. The Timbalier Subbasin experiences substantial

subsidence and is essentially isolated from major freshwater and sediment

inputs. Marsh loss rates are high due to the resulting sediment deficit,

saltwater intrusion along the Houma Navigation Canal and other canals, historic

oil and gas activity, and natural deterioration of barrier islands, which

contributes to the inland invasion of marine tidal processes (including erosion,

scour, and saltwater intrusion). The subbasin is rapidly converting to an open

estuary.

In recent years, the Penchant and Verret Subbasins have experienced

significant freshwater impacts from the Atchafalaya River. Historic wetlands

loss resulting from subsidence, saltwater intrusion, and oil and gas activity

appears to have moderated, but areas of cypress swamp (Verret) and flotant marsh

(Penchant) are experiencing stress from high water levels in the Penchant

Subbasin, the use of freshwater and sediment resources is not being maximized.

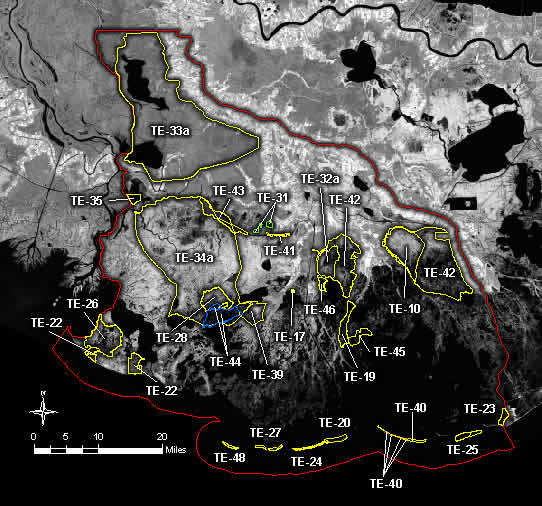

Projects in the Terrebonne Basin

Summary of the Basin Plan

STUDY AREA

The Terrebonne Basin is bordered by Bayou Lafourche on the east, the

Atchafalaya Basin floodway on the west, and the Gulf of Mexico on the south. The

Terrebonne Basin is divided into four subbasins--Timbalier, Penchant, Verret,

and Fields, as shown in Figure TE-1. The basin includes all of Terrebonne

Parish, and parts of Lafourche, Assumption, St. Martin, St. Mary, Iberville, and

Ascension parishes.

EXISTING CONDITIONS AND PROBLEMS

The Terrebonne Basin is an abandoned delta complex, characterized by a thick

section of unconsolidated sediments that are undergoing dewatering and

compaction, contributing to high subsidence, and a network of old distributary

ridges extending southward from Houma. The southern end of the basin is defined

by a series of narrow, low-lying barrier islands (the Isles Dernieres and

Timbalier chains), separated from the mainland marshes by a series of wide,

shallow lakes and bays (e.g., Lake Pelto, Terrebonne Bay, Timbalier Bay).

The Verret and Penchant Subbasins receive fresh water from the Atchafalaya

River and Bay, while the Fields Subbasin gets fresh water primarily from

rainfall. The Timbalier Subbasin gets fresh water from rainfall and from

Atchafalaya River inflow to the GIWW via the Houma Navigation Canal (HNC) and

Grand Bayou Canal; it has the most limited fresh water resources in the entire

Deltaic Plain.

The Terrebonne Basin supports about 155,000 acres of swamp and almost 574,000

acres of marsh, grading from fresh marsh inland to brackish and saline marsh

near the bays and the gulf. The Verret Subbasin contains most of the cypress

swamp (118,000 acres) in the Terrebonne Basin. The northern Penchant Subbasin

supports extensive fresh marsh (about 166,000 acres), including a predominance

of flotant marsh, with 98,000 acres of intermediate and brackish marsh in the

Lost Lake-Jug Lake area and about 17,000 acres of saline marsh to the south.

Fresh marsh is also dominant in the Fields Subbasin (approximately 23,000

acres). The Timbalier Subbasin grades from fresh marsh in the northern part of

the subbasin to saline marsh near the bays, but is dominated by brackish (71,000

acres) and saline (153,000 acres) marsh types.

Of the four subbasins, only the Fields Subbasin experiences problems which

are local and relatively minor. The Timbalier Subbasin experiences substantial

subsidence and is essentially isolated from major freshwater and sediment

inputs. Marsh loss rates are high due to the resulting sediment deficit,

saltwater intrusion along the Houma Navigation Canal and other canals, historic

oil and gas activity, and natural deterioration of barrier islands, which

contributes to the inland invasion of marine tidal processes (including erosion,

scour, and saltwater intrusion). The subbasin is rapidly converting to an open

estuary.

In recent years, the Penchant and Verret Subbasins have experienced

significant freshwater impacts from the Atchafalaya River. Historic wetlands

loss resulting from subsidence, saltwater intrusion, and oil and gas activity

appears to have moderated, but areas of cypress swamp (Verret) and flotant marsh

(Penchant) are experiencing stress from high water levels in the Penchant

Subbasin, the use of freshwater and sediment resources is not being maximized.

Figure TE-1. Basin and Subbasin Boundaries, Terrebonne Basin.

FUTURE WITHOUT-PROJECT CONDITIONS

Under a no action alternative, and assuming continued losses at the 1974-1990

rate, existing wetlands would be lost in the magnitude outlined in Table TE-1.

The projected loss of more than half the Timbalier marshes in 50 years could be

exceeded, because of the expectation that protection by existing barrier islands

will cease within a few years to a few decades. The actual loss of Penchant

marshes may be less than shown, because of benefits from Atchafalaya fresh water

and sediment that have been increasing.

With no action, the Timbalier Subbasin will become 75 percent (or more) open

water, with the shore reaching as far north as the suburbs of Houma. In the

Penchant Subbasin, losses will likely be concentrated in the northern and

central sectors, further exposing areas of open water and broken marsh. The

inefficient use of Atchafalaya fresh water and sediments will continue to

squander this significant resource. With continued high marsh losses, biological

productivity and diversity will decrease. With loss of critical habitat for

commercially and recreationally important fish, shellfish, and furbearers, as

well as for endangered species, fish and wildlife dependent economic activities

will decline. Flooding problems will increasingly impact economic activities

throughout the Terrebonne Basin, leading to grave consequences for the oil and

gas industry and for other human infrastructure.

Table TE-1.

Projected Marsh Loss

Projected Loss in 20 years Projected Loss in 50 years

Subbasin (Acres) (Percent) (Acres) (Percent)

Timbalier 60,100 22 150,250 56

Penchant 24,900 8 62,250 20

Verret Not Available Not Available

Fields 2,800 11 7,000 29

Total 87,800 14 219,500 36

BASIN PLAN

In the Timbalier Subbasin, protection and restoration of the barrier islands

(Isles Dernieres and Timbalier Islands) requires immediate and extensive action,

because these landforms provide protection for mainland marshes, and destruction

of many of the islands is imminent. Interior marshes will also be protected

through a hydrologic restoration zone which will be developed in the vicinity of

the independently proposed Terrebonne Parish Comprehensive Hurricane Protection

system. In this zone, fresh water and sediment will be used along with marsh

protection and passive hydrologic restoration structures to enhance and restore

overland and sinuous channel flow. A related action in the Timbalier Subbasin is

a proposed barrier to saltwater intrusion in the Houma Navigation Canal.

In the Penchant Subbasin, Atchafalaya River fresh water, sediment, and

nutrients will be better utilized through hydrologic restoration to protect

marshes and reduce loss rates. To the extent possible, actions will restore

historic flow

Figure TE-2: Terrebonne Basin, Strategy Map

patterns and conveyance channels and improve the distribution of

sediment-laden water. These actions in Timbalier and Penchant are considered

critical for short-term implementation.

In the Penchant Subbasin, at least one major diversion would be built from

the Atchafalaya River to bring fresh water and sediment into the subbasin. This

is contingent upon adequate addressing of flood problems in the subbasin.

Because these actions will not cover all areas of concern, a supporting

short-term strategy is to consider site-specific, small-scale projects in all

subbasins where there is a critical need for wetlands protection or restoration,

or a significant opportunity for wetlands creation. In the short term,

demonstration and pilot projects must also be conducted to develop or test

methods and approaches needed for implementing long-term strategies.

In the Timbalier Subbasin, long-term restoration depends on cost-effective

importation of sediment by diversions or dedicated dredging, which makes

demonstration of sediment extraction, transport, and placement technologies a

priority. In addition, the possibility of diverting Mississippi River water and

sediment into Bayou Lafourche as a conduit to the Timbalier Subbasin (as well as

to the Barataria Basin) must be evaluated, and will be part of a larger study.

The establishment of a Mississippi River sediment budget and distribution

options, to be initiated by the Task Force immediately, will greatly aid in this

effort.

In the Verret Subbasin, pumping to lower water levels is required to protect

the swamp forests. This is a long-term strategy, because significant planning

activities must precede its implementation. In addition, this action cannot

occur until provisions are made for managing outfalls in ways which will not

exacerbate flooding in the Penchant Subbasin.

In summary, the Terrebonne Basin Plan includes both a short-term and a

long-term phase. The short-term phase focuses on immediate actions needed to

protect vulnerable marshes from the proximal causes of loss in the Terrebonne

Basin (saltwater intrusion, erosion, and other consequences of significant

hydrologic modifications) using a combination of restoration techniques

(especially hydrologic restoration and small-scale marsh creation) in the most

critical areas or key locations, and barrier island protection. Successful

implementation of short-term strategies will reduce rates of wetlands loss, and

will provide the foundation for longer-term strategies. The long-term phase

focuses on wetlands gains through sediment diversion and import, with the intent

of encouraging development of a sustainable wetland ecosystem. Long-term

strategies are critical to addressing the primary problem of sediment starvation

associated with high subsidence and loss of fluvial inputs, and to achieving no

net loss of wetlands in the basin.

Projects included in the Terrebonne Basin Plan are listed in Table TE-2.

Table TE-2 indicates the classification (e.g., critical, supportive,

demonstration), estimated benefits and costs, and status of these projects. The

main elements of the Terrebonne Basin strategy are displayed in Figure TE-2.

A description of the Terrebonne Basin plan formulation process is contained

in Appendix E. A complete listing of projects that have been proposed for the

Terrebonne Basin can be found in Appendix E, Table 5, including those that were

combined with other projects, or were not included in the plan for reasons

stated in the appendix. More detailed information on each selected project also

is provided in Appendix E.

COSTS AND BENEFITS

An expenditure of approximately $310,000,000 will directly create, protect,

or restore more than 32,000 acres of wetlands in the Terrebonne Basin (Table

TE-3), with additional wetlands enhancement increasing the benefit to more than

100,000 acres (see Table TE-2). In the Timbalier Subbasin, implementation of

critical and supporting projects which compose the short-term phase of the

selected plan will offset almost one third (31 percent) of the predicted marsh

loss by direct protection, restoration, or marsh creation. Additional efforts

will be needed to achieve a sustainable wetlands environment in the Timbalier

Subbasin, making the long-term phase of the plan--sediment import projects--and

associated demonstrations necessary.

Table TE-3

Estimated Benefits and Costs of the Selected Plan 1/2/

Acres Created, Percent

Protected, or Loss

Restored Prevented Cost ($)

Critical Short-Term

Timbalier Subbasin 16,349 27 225,733,000

Penchant Subbasin 11,406 46 57,272,000

Fields Subbasin na na na

Subtotal 27,755 32 283,005,000

Supporting Short-Term

Timbalier Subbasin 2,269 4 16,971,000

Penchant Subbasin 2,218 9 9,018,000

Fields Subbasin 61 2 815,000

Subtotal 4,548 5 26,804,000

Total 32,303 37 309,809,000

1/ Only projects with estimates of both benefited acres and cost were

included in the summary.

2/ Neither costs nor benefits are now known for the key strategies in the

Verret Subbasin.

na--not applicable (no critical projects in the Fields Subbasin).

In the Penchant Subbasin, implementation of the short-term phase of the

selected plan, including both critical and supporting projects, will avert or

offset approximately 55 percent of the predicted loss. After hydrologic

restoration is in place and flood control problems are addressed, the long-term

strategy of diverting substantial amounts of Atchafalaya River water and

sediment into the subbasin can be implemented, conceivably leading to no net

loss of wetlands.

Although the costs and benefits for the key strategies in the Verret Subbasin

are not currently known, the scale of the strategy in Verret is appropriate to

the scale of stress on the cypress swamps and addresses the major portion of the

problem. Only site-specific, small-scale projects are currently planned for the

Fields Subbasin.

Back to Top

Dynamics of the Basin

The Terrebonne Basin covers approximately 1,712,500 acres of southern

Louisiana, including about 728,700 acres of wetlands (figure 22). About 96% of

the wetlands in the Terrebonne Basin are privately owned. The USFWS recently

established the 4,618-care Mandalay National Wildlife Refuge located in the Lake

Hatch area of central Terrebonne Basin. State-owned land is represented by

wildlife management areas (WMA's) and refuges covering about 28,244 acres in the

southeastern basin. The state leases additional lands, which it manages as

WMA's.

The USACE has constructed and maintains navigation channels in the Terrebonne

Basin, which cross sensitive wetland areas. Vessel traffic in the channels is a

major source of erosion in wetland areas. These channels also provide an avenue

for saltwater intrusion into fragile wetland areas, thereby changing the

salinity and nature of these wetlands and leading to deterioration and

conversion to open water.

Subsidence occurs at different rates throughout the inactive deltaic plain as

unconsolidated sediment dewaters and compacts. Subsidence in the Terrebonne

Basin is among the highest in Louisiana at 0.42 inches/year (Penland et al.

1989). As subsidence occurs, flooding in wetlands increases, contributing to

marsh loss. Subsidence also impacts the Terrebonne Basin's barrier island chains

(Isles Dernieres and Timbalier Islands) that potentially provide protection to

fragile inland wetlands. These islands absorb the impact of wave action from the

Gulf of Mexico and potentially inhibit erosion of inland shorelines. As these

islands shrink from subsidence, inland wetlands may become more vulnerable to

the erosive forces of the Gulf of Mexico. Hurricane Andrew in 1992 had a severe

impact on these islands, and without restoration, Louisiana's barrier islands

will disappear. The extent of protection to interior areas by barrier island is

currently being modeled through the Louisiana Barrier Shoreline Feasibility

Study.

An abundant supply of fresh water and sediment is an important component to

the health of wetlands in the Terrebonne Basin. These resources are supplied to

the northern and western areas of the basin by the Atchafalaya River. The

formation of the deep organic soils of this basin is a result of vegetative

deposition, typically below ground with very limited mineral matter (Nyman et

al. 1992, 1993a, 1993b, 1993c, 1994). The primary source of fresh water to the

Timbalier subbasin (in the basin's southeast region) is precipitation, which

averages 65 inches/year in this area. On average, precipitation is greater than

evaporation; however, in the summer months evaporation exceeds precipitation.

Sediment input into the southeast Terrebonne Basin occurs only when the

Atchafalaya River stage is high and river waters flow down the Houma Navigation

Canal. These inputs are small relative to the substantial influence of saltwater

intrusion and high subsidence rates in the area. Overall, the southern basin has

the most limited freshwater resources and sediment influx in the entire inactive

deltaic plain. The absence of overflows from the riverine sources accounts for

these freshwater and sediment deficits.

The hydrology of the Terrebonne Basin has been severely influenced by

construction of canals and levees. As a result saltwater intrusion has occurred

and has led to erosion and ultimate conversion of many areas from fresh marsh to

salt marsh or open bodies of water. Barrier islands have also been impacted by

erosion. As these islands have absorbed the wave energy of the Gulf of Mexico,

they have continued to erode away.

Since 1932, the Terrebonne Basin has lost approximately 20% of its wetlands

(Dunbar et al. 1992, figure 27). Current loss rates range from approximately

4,500 (Dunbar et al. 1992) to 6,500 (Barras et al. 1994) acres/year. This loss

amounts to up to 130,000 acres during the next 20 years. One-third of the

Terrebonne Basin's remaining wetlands would be lost to open water by the year

2040. Losses would be concentrated in the lower basin, where Timbalier Bay could

become open to the Gulf of Mexico and the existing shoreline could retreat as

much as 10 miles north (LCWCRTF 1993).

Back to Top

Discussion

Project implementation in the Terrebonne Basin to date has focused on rebuilding barrier

islands and creating, protecting, and restoring wetlands in localized areas. Since no

projects have been completed in the Terrebonne Basin, there are no results of project

performance. Once completed, almost 7,000 acres are anticipated to directly benefit

from wetland creation, restoration, and protection through CWPPRA. Additional indirect

benefits may include mainland marsh protection resulting from the CWPPRA barrier island

projects.